Aha Moments

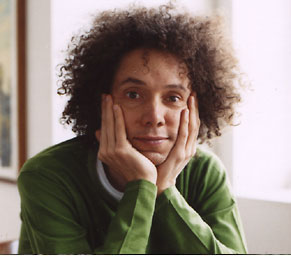

I’m reading the new Malcolm Gladwell book David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, and I’m getting a lot out of it,with two points really hitting home.

My first “Aha” came from Gladwell’s description of an extremely successful Hollywood mogul and the values and experiences that formed the character traits that led to his monumental accomplishments. He, like myself, came from a lower-middle-class family,with grandparents who immigrated to America looking for better lives and to find a safe haven from the religious persecution in Eastern Europe and the economic horrors that occurred all over the planet in the late 1800s and early 1900s.His parents, like mine and everyone else’s of our generation, forged their spirit, values, and temperament by living through the effects of World War I, which started in 1914 and ended in 1918. Eleven years later came the Great Depression and ten years after that came World War II. No American was untouched by these three events, which shaped the American ethic of the people that Tom Brokaw’s book referred to as “the greatest generation.”

None of what our parents learned as they grew up was wasted on my generation. As adults, most of our parents struggled to make ends meet.They taught us the value of turning off the lights, not wasting food, and knowing that when we became adults we would work hard, raise our own families, and live independently. They instilled in us values of self-sufficiency, a strong work ethic, and the understanding that we had to make it on our own.

When I was a kid, it was common for children to have paper routes or work around the house or the neighbor’s house to earn money. When I was thirteen, every day after school I would “thumb a ride,” or hitchhike,from where I lived to a gas station about five miles away, where I met Willy Kurtzman, a 50-year-old American version of Fagin from Dickens’s Oliver Twist, who drove me and a carload of other teenage boys to new housing developments where he told us to knock on doors and ask the young housewives to “help us out” by buying magazines. In hindsight, I see that he was training us to become junior conmen, but it was probably the best business experience a thirteen-year-old could get if you didn’t count the “boys’ club needs your help” speech he taught us. The boys’ club didn’t exist.

Both the movie mogul and I learned to be tough, clever, tenacious, and to think on our feet. As adults, we both grew wealthy, and we both wanted better lives for our kids, and herein lies the first “Aha!”

When we became parents, times had changed and we had changed.We both must have felt that living the American Dream was our destiny and perhaps even our duty. Our kids grew up in the lap of luxury, and while we thought we were giving them every advantage, it didn’t work out that way.

How could I drive a luxury car, live in a mansion, send my kids to exclusive private schools, and then tell my kids that they can’t have the clothes, toys, or luxuries they want? “Do as I say, not as I do” never worked for me. It didn’t occur to me that as children, it was appropriate for them to have to learn the same lessons I had learned as a kid. That wasn’t in my picture of how things should be once I could afford a luxurious lifestyle.

Gladwell points out that people who grow up poor and later come into riches are unprepared for the life they believe they are supposed to live as super wealthy. They plain don’t know how to handle that new culture. I certainly didn’t. Gladwell refers to this phenomenon as similar to refugees from a third-world country who are dropped into living a royal life.Growing up, my only experience of what it meant to be wealthy came from the Depression-era movies that filled the early days of TV in the 1950s.

Many of these old movies were about rich people living in mansions, dressing well, and driving Rolls Royces. This gave me the idea that being wealthy meant I should have a mansion, dress well, and drive a Rolls Royce.I’d never even stepped inside a mansion until I bought one. It never occurred to me that the movies were escapist fare, not road maps for how to live life.

The second “Aha” for me in Gladwell’s book was his observations about how misfortune in a child’s life can ultimately develop into a blessing in disguise. He explains how dyslexic children often create strategies to compensate for their weaknesses, and how over time those strategies turn into incredible strengths leading to a kind of master-fulness that brings them into the winner’s circle. Gladwell uses some of America’s most iconic success stories to explain how a learning disability can force children to find other, nontraditional strategies to compensate for their inabilities. For example, a highly successful attorney who as a child had trouble reading because of dyslexia developed shortcut study skills, extremely good verbal skills, and an ability to convince his teachers that he knew the material even if he didn’t do well on tests. All of this resulted in his becoming an extraordinary litigator, masterful at arguing his cases in court.

Gladwell, also explains how children who lost a parent in their formative years (as I did) are statistically far more successful than their peers who had two parents.In my case, losing my father so early resulted in my growing up as a “child-adult” who had to take care of myself. In doing so, I learned skills at eleven that others wouldn’t learn for many years. Gladwell, in his previous book Outliers, made the point that it takes 10,000 hours to become masterful. With “necessity being the mother of invention” forcing me to take charge of adult situations after my father’s death, I was still a teenager when I put in the hours to become masterful at coping strategies for taking care of my mother, my brother, and myself. These turned out to be the exact skills that made me wealthy.

Unfortunately, of course, there was another side to the coin.Like the “wealth refugees” who are wealthy but whose abundance can rob their children of the values that made the parents a success, losing my father early in life, while catalyzing me to become masterful financially,not only robbed me of the experience of having a dad but also of knowing how to be a dad.

The desire to prevent my children from feeling the kind of emotional pain I felt as a child over the loss of my father resulted in far more than the “poor little rich kid” curse for my children,because I never wanted to be tough on them. I perceived being tough on them—saying no (even when I knew I should say no) and making sure there were consequences for inappropriate behavior (even when I knew consequences were needed)—as causing my children to be angry at me, and I equated their being angry at me with losing our bond. Thus I viewed that being “tough” on them would mean they would lose me and I would lose them.

Between never wanting my kids to feel the emotional pain I experienced as a child and living a “high-on-the-hog” American Dream lifestyle, I simply didn’t know how to be the father I wanted so very much to be.

I realize now that the examples I set were not healthy ones. I was in a “refugee” state and didn’t know it; I was full of pain and fears from losing my father, and I didn’t know how this was affecting me as a father. I had nobody to ask, and it’s taken me years to understand it. I’m grateful for Malcolm Gladwell’s book for helping me and others to see this

- 12 Dec, 2013

- Posted by Steve Fogel

- 0 Comments

COMMENTS